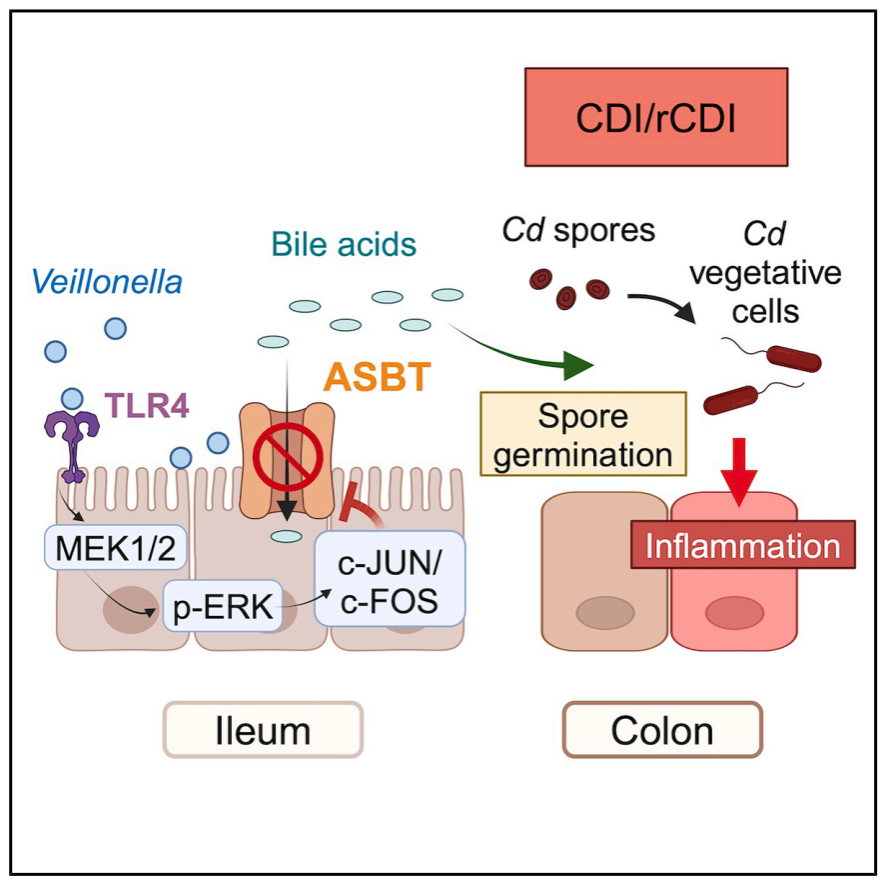

Crohn’s disease is a severe inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with no known cure. Individuals with Crohn’s disease face an increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), which significantly worsens symptoms. On August 22, 2025, a research paper titled “Veillonella intestinal colonization promotes C. difficile infection in Crohn’s disease” was published online in Cell Host & Microbe by co-corresponding authors Li Min from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Nursing, Cao Zhijun from Renji Hospital, and Michael Otto from the National Institutes of Health, USA. Through a prospective observational clinical study combined with an animal model of intestinal inflammation, the study found that intestinal colonization by the oral commensal bacterium Veillonella promotes CDI in Crohn’s disease. In mice, Veillonella parvula suppresses the expression of the primary bile acid transporter ASBT, inhibiting bile acid reabsorption. Similarly, in Crohn’s disease patients, increased Veillonella abundance is associated with elevated bile acid metabolism. The increased availability of bile acids in the intestinal lumen triggers C. difficile germination. V. parvula expresses a highly pro-inflammatory lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that activates transcription factors c-Jun and c-Fos, which regulate ASBT expression. These findings highlight how oral commensal bacteria exacerbate intestinal disease and provide a pathway for designing therapies to treat CDI in Crohn’s disease patients.

Crohn’s disease is a common form of IBD, characterized by symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and intestinal obstruction. Unlike ulcerative colitis (another major type of IBD), Crohn’s disease typically affects the entire digestive tract and causes intermittent rather than continuous inflammation. As of 2020, the global prevalence of IBD was 0.75%, projected to rise to 1.0% by 2030. Approximately 37%-59% of IBD cases are Crohn’s disease. Although suspected to result from a combination of immune, environmental, genetic, and bacterial factors, the etiology of Crohn’s disease remains largely unknown. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiome is a key feature of IBD, including Crohn’s disease, but the mechanisms of host-microbiome interactions in IBD and Crohn’s disease are only beginning to be elucidated, primarily focusing on immune responses. How specific microbes influence other microbes in the IBD environment, leading to IBD or infections, remains largely unknown.

It is well established that gut dysbiosis, often triggered by antibiotic treatment, is a major risk factor for CDI, the most deadly antibiotic-resistant disease in developed countries. Globally, there are approximately 500,000 CDI cases annually. Clostridium difficile, an obligate anaerobic Gram-positive bacterium, typically colonizes the human gut at low levels but proliferates when the gut microbiome is disrupted, such as after antibiotic intervention. C. difficile causes inflammation and damage by secreting enterotoxins and cytotoxins. CDI symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, pseudomembranous colitis, and, in severe cases, toxic megacolon and death. CDI is typically treated with antibiotics but is prone to recurrence. Recurrent CDI (rCDI) refers to toxin-positive C. difficile reappearing within 2-8 weeks after initial CDI resolution. CDI not only increases hospitalization duration, exacerbates healthcare burdens, and reduces quality of life for Crohn’s disease patients but also significantly elevates their mortality rates.

Mechanism Diagram (Source: Cell Host & Microbe)

Research on the adverse effects of gut dysbiosis often focuses on the absence of symbiotic “beneficial” bacteria. In CDI, C. difficile overgrowth results from a lack of colonization resistance due to the absence of such bacteria, forming the basis for the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in treating CDI. Conversely, the potential impact of disease “pathogens”—bacteria that may enhance pathogen proliferation and effects—is often overlooked. Recent studies have shown that enrichment of Enterococcus in the gut of CDI patients can promote C. difficile proliferation by producing fermentable amino acids, indicating that microbial interactions play a critical role in CDI progression.

This study systematically reveals the key role of the oral commensal bacterium Veillonella in CDI development in Crohn’s disease patients. It elucidates a molecular mechanism whereby Veillonella LPS inhibits ileal ASBT-mediated bile acid transport and reabsorption by activating the TLR4-MAPK-cFOS signaling pathway, leading to the accumulation of conjugated bile acids in the cecum and driving C. difficile spore germination and infection. This research not only expands understanding of the mechanisms underlying cross-domain colonization by oral bacteria and gut infections but also offers new directions for clinical prevention and treatment.